Este artículo no contiene spoilers.

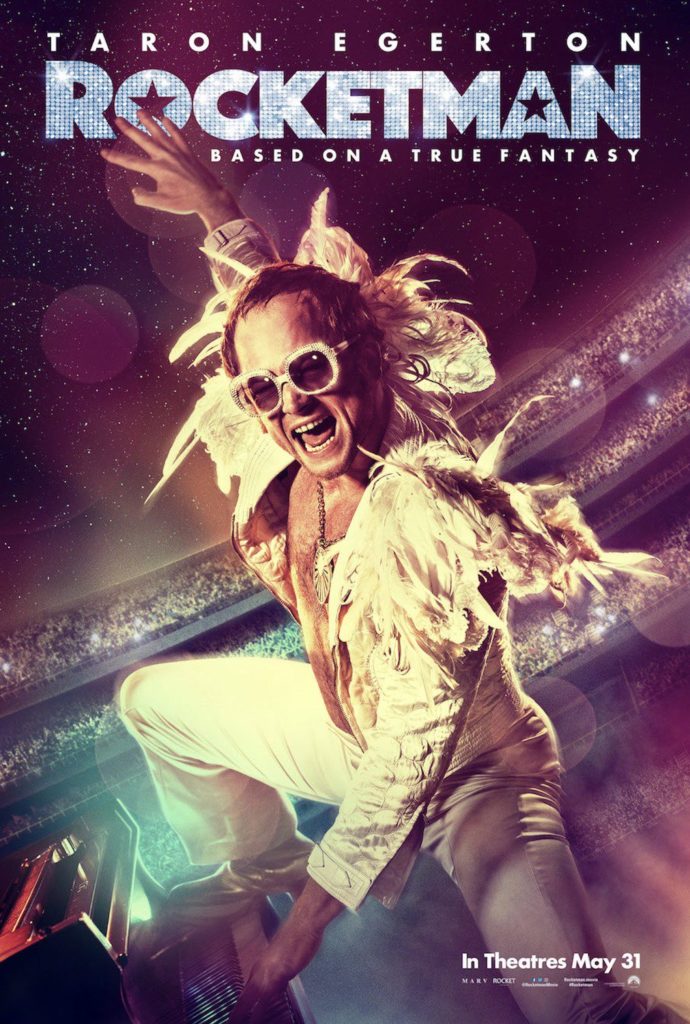

“Rocketman” (2019) es la segunda superproducción cinematográfica contemporánea centrada en una estrella cuya vida es el epítome de los excesos asociados con la frase “sexo, drogas y rock & roll”: Elton John. Es la sucedánea de “Bohemian Rhapsody”, y ese dato es de particular relevancia ya que ambas comparten director: el británico Dexter Fletcher. La principal diferencia es que mientras “Bohemian Rhapsody” fue planteada como una biografía convencional, “Rocketman” ha sido propuesta como un musical en el cual la obra de Elton y el letrista Bernie Taupin deviene en el artilugio narrativo para contar una historia “basada en una fantasía verdadera”.

Y aún con esa particularidad, con ese supuesto carácter ilusorio que se explicita ya desde el principio (y el cual es concomitante con el personaje creado por Elton a mediados de los 70s, el “Capitán Fantástico”) no deja de ser llamativo cómo “Rocketman” es más fidedigna a la realidad que “Bohemian Rhapsody”. Ésta se tomó una serie de libertades narrativas que oscilaron entre las simplemente estéticas, como ser la época en la cual Freddie Mercury comenzó a lucir su icónico bigote, a las totalmente injustificables. El ejemplo más característico es la fecha del diagnóstico cero positivo de Mercury, el modo y momento en que se lo hizo saber a sus compañeros de banda, y la instancia creativa en la que supuestamente se encontraba Queen en aquel entonces – todo por completo desdibujado, para imprimirle a la película un dramatismo adicional que no era necesario. La vida de Freddie ya era lo suficientemente cinematográfica y dramática si se narraba tal cual había sido. Esto significó la mayor decepción para los verdaderos adeptos de Queen, y el objeto más recurrente (y con más fundamento) de crítica a “Bohemian Rhapsody”.

Quizá por eso las inexactitudes factuales en “Rocketman” brillan por su ausencia. La principal (y la única que me hizo dar un salto de asombro en la butaca por su inverosimilitud) es la referida al origen del nombre “Elton John” – como posiblemente sepan, Elton en realidad se llama Reginald Kenneth Dwight. La escena en la que se decanta por su nombre artístico está planteada de modo simpático, y no se puede negar que funciona bien. Y la idea de éste artículo es no incurrir en spoilers de ninguna índole. Pero tienen que saber (y esto es algo ampliamente documentado y constatado) que el nombre “Elton John” deriva de Elton Dean y Long John Baldry, integrantes de Bluesology – la primera banda en la cual Elton se desempeñó como tecladista. Y quiero detenerme en lo que ocurre en la película con el personaje de Long John Baldry. O para ser más exacto, en lo que no ocurre – Baldry no existe en el film. Y esa omisión es desconcertante, ya que su influencia en la vida de Elton tuvo un alcance muy amplio, el cual trascendió lo meramente musical. Baldry fue clave en el despertar sexual de Elton John, y ese papel en la película es desempeñado por otro músico. Sepan que eso no ocurrió de esa forma.

Dejando esto de lado, no hay personajes inventados ni fusionados (como sí ocurre en “Bohemian Rhapsody”), y figuran todos quienes tuvieron alguna injerencia en la vida de Elton John, con otra honrosa excepción: Paul Buckmaster, el responsable de los arreglos de orquesta en todos los álbumes desde “Elton John” (1970) hasta “A Single Man” (1978), y en algún disco posterior, como ser “Made In England” (1995)

Todos los demás están representados en la película de algún modo u otro, incluyendo la banda “clásica” de Elton John, y el productor Gus Dudgeon figura en la escena cuando graban “Your Song” (escena donde perfectamente podría haber aparecido Buckmaster).

Si me centro en ésta persona es porque fue uno de los tres pilares donde se apoyó el ascenso al estrellato de Elton, junto a la banda “clásica” conformada por Davey Johnstone, Dee Murray y Nigel Olsson y el productor Gus Dudgeon – fue recién cuando Buckmaster orbitó a la esfera creativa de Elton que se materializaron sus primeros éxitos trasatlánticos, no antes.

La trama en “Rocketman” avanza a través de flashbacks. Cuando inicia la película, Elton llega a una terapia de grupo ataviado de un modo metafóricamente espléndido, y de inmediato somos participes de cómo alcanzó esa instancia especialmente conflictiva en su vida.

El propio Elton manifestó que “la película no es apta para todo público porque mi vida no fue apta para todo público”. Él mismo la supervisó, aunque existen versiones muy encontradas sobre qué papel realmente desempeñó en su dirección artística y contenido – algunos dicen que estuvo presente durante el rodaje, otros que hizo poco más que consentir que se narrara la historia de su vida, dándole al director plena libertad creativa. A los efectos, la película no tiene paliativos en materia de drogas y sexo, y ya pasó a la historia como el primer blockbuster que incluye una escena de carácter explícito entre dos hombres.

Por otro lado, me sorprendió el rol cuasi-mesiánico del letrista Bernie Taupin – no me parece bien hablar sin conocimiento de causa, pero no me cuadra que alguien conocido por su misoginia y frecuente misantropía haya podido ser semejante faro moral para Elton.

Quienes no aparecen ni física ni musicalmente son los otros letristas que colaboraron con Elton como Gary Osborne y Tim Rice. Eso quiere decir que canciones como “Blue Eyes”,”Ball & Chain”, “Little Jeannie” y “Can You Feel The Love Tonight” fueron omitidas.

Y podrían no haberlo sido, ya que la película no solo es un musical, sino que sus canciones no siguen una cronología real – son funcionales a la trama. Así, “Rocketman” inicia con “The Bitch Is Back”, y luego llega “I Want Love” de “Songs From The West Coast” (2001). Me sorprendí cuando empezó a sonar, y me ilusioné con que “Rocketman” quizá no sería una concatenación de éxitos. Pero eso es lo que terminó siendo, y lo entiendo. Las única otras “rarezas” fueron “Amoreena” del disco conceptual “Tumblewood Connection” (y qué bueno que lo hayan referido al menos de éste modo, ya que ese álbum fue el cimento de Elton John como creador de obras consistentes en sentido unitario) y “Rock & Roll Madonna” – un tema que utiliza el recurso de añadir un público en vivo para dotarlo de una cuota adicional de dinamismo. Éste recurso sería empleado luego en ”Bennie & The Jets” de manera mucho más memorable, convirtiendo al supuesto público en parte integral de la canción mediante la percusión que provee con sus palmas.

Me generó entre pena y extrañeza que se obviaran los discos autobiográficos “Captain Fantastic” (1973) y “The Captain & The Kid” (2013) – en la primera escena con Bluesology, poco menos me puse a tararear “Gotta Get A Meal Ticket” en antelación. Y los últimos treinta minutos se podrían haber condensado en cinco con “Made In England”, del álbum titular de 1995.

Quizá los productores sintieron que incluir música de deliberado corte biográfico en una autobiografía podía ser lesivo para el impacto de la película, o diluir en algo el efectismo de la narración. De cualquier modo, canciones como “Bitter Fingers” o “Better Off Dead” merecían un lugar en la historia, no porque hubieran “salvado” la película, sino porque representan el acervo más dramático a nivel compositivo de Elton John en el apogeo de su carrera, cuando alcanzó a tener siete discos consecutivos en el número uno de las listas de ventas.

Es necesario puntualizar que la música de “Rocketman” es interpretada por el reparto – solo se escucha a Elton John al final, en una nueva composición que canta a dúo con el actor que lo personifica, Taron Egerton (se titula “(I’m Gonna) Love Me Again”, y es un tema francamente bueno). Ésta es quizá la diferencia más sustancial en materia de contenido artístico con “Bohemian Rhapsody”, que proponía una experiencia similar a estar en un concierto de Queen (y ameritaba con creces ir a verla a una sala de cine). Y explica por qué “Rocketman” ya casi no esté en ninguna sala. Pensé que iba a durar al menos un mes más – aún dejando de lado el contexto de los premios Oscar, “Bohemian Rhapsody” tuvo una permanencia descollante en cartelera.

Asimismo, me parece importante mencionar que no soy un fan de Queen, ni de Elton John. Aprecio y estimo a ambos; posiblemente algo más a Elton – tengo casi toda su discografía, y eso incluye sus innúmeros deslices artísticos en la década de los 80s, y los discos básicamente monocordes que viene publicando desde los 90s. Elton fue el primer artista por el que viajé a Argentina, como así también el único artista que vi en vivo con mi madre en Uruguay (2013).

Sin embargo, es innegable que “Bohemian Rhapsody” tiene un carisma que la hace atractiva para todo público. Por el contrario, “Rocketman” me pareció concebida estricta y únicamente para fans de Elton John. No sé si le gane muchos nuevos adeptos, y no he visto reediciones de sus álbumes en disquerías, como sí he visto (y en cantidades y cualidades maravillosas) de Queen. Pero “Rocketman” sí funciona (¡y de qué modo!) como publicidad para su actual gira despedida, y para su autobiografía, la cual tiene fecha de edición tentativa para octubre de 2019. No creo tampoco que “Rocketman” sea galardonada con ningún Oscar, pero lo que sí ha hecho es reafirmar la curiosidad que granjeó “Bohemian Rhapsody” por la vida de muchos de los protagonistas culturales del siglo XX. Todo indica que los próximos destinatarios de blockbusters de Hollywood van a ser Prince y David Bowie, mientras que otros como Mötley Crüe, INXS y Depeche Mode ya están recibiendo la atención de servicios como Netflix y Showtime.