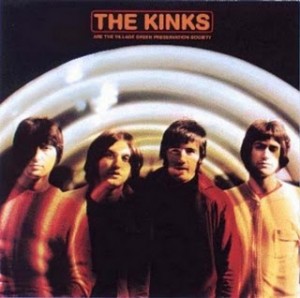

Issued In 1968, “The Village Green Preservation Society” Was The First Album Over Which The Kinks Had Full Creative Control.

Freed from the onerous contract they once had signed with American expatriate Shel Talmy, The Kinks finally could begin pursuing Ray Davies’ vision to the full. The year was 1968, and by that time the band had been banned from entering the US owing to their unmanageable onstage behavior. (The incident in which Mick Avory trounced Dave Davies with his hi-hat and fled as the guitarist lay in a pool of blood was most likely the final straw for the detractors of the band with the risqué name.)

Being barred from playing in the country where the big income was for any performer invariably made Ray look for his themes closer to where he was. And (as I think I have said elsewhere) the man was an all-out nostalgic in any case. There was nothing more coherent to him than looking back and romanticizing. And while the band’s previous record (“Something Else”) had actually indicated that his vision of England was just too settled, it also showcased what a deft describer of characters and incidents he was.

That was the context in which The Kinks’ next album was gestated. Ray took his romanticism to the extreme and single-handedly wrote an album mourning the passing of all these traditions he saw as decidedly British. He focused on the nominal village and turned the whole band into protectors of these traditions, painting one sketch after the other of small town characters and the fate that befell them as they either remained where they were (“Johnny Thunders”) or tried to break into the larger world (“Do You Remember Walter?”) . Of course, the weight of the world was felt on the delicious title track, which (like many others such as “Phenomenal Cat” and “Animal Farm”) had a truly startling childlike quality to it. More than often, you feel as if the narrator has chosen to remain in the verge of innocence, and that he is never going to venture a single inch forwards. And both the songs “Village Green” and “Picture Book” make it clear how disheartening the way ahead is, with the protagonists becoming unable to enjoy either the places they have arrived at, or the places they have come from.

Ray wrote everything this time around (brother Dave had no writing credits, but he had a devilish cameo on “Wicked Anabella”) and he even acted as the record’s producer. If “The Village Green Preservation Society” makes you feel like you are listening to a Ray Davies’ solo album, then that is because you are. That is, you are listening to a single voice throughout. Ray Davies was to begin running the show from this point onwards, and the band was to produce some of its better works under his aegis.

Musically, the album is very delicate, and (personally) I find it quite adorable. There are acoustic guitars aplenty, flutes, droning organs on “Sitting By The Riverside”, a hazy harpsichord that washes over “Village Green”, a number in which Ray opts to recite rather than to sing (“Big Sky”)…

Were it not for “Starstruck” and the bluesy “Last Of The Steam-Powered Trains” (in which Dave also plays the harmonica), it would be tricky to call this a “rock” record. Even then, it is difficult to think of it in such terms. And it is easy to see why it did not fare very well when it was first issued. Just look at the albums either side of it. On the one hand, you have The Beatles’ “Sgt. Peppers”, on the other you have The Who’s “Tommy”. The latter in particular dealt with loss of innocence in a way that could resonate far more profoundly with the flower generation. Sadly, there wasn’t room for something like “The Village Green Preservation Society” on the charts back then. It was an album whose charms could only be appreciated in retrospect.

Perversely fitting for a praiser of the past like Ray Davies, wouldn’t you say?

Rating: 8.5/10

Pingback: The Kinks (Compilation Album) | MusicKO

Pingback: Lola Vs. The Powerman And The Moneygoround (The Kinks) – Album Review | MusicKO